Maximilian

JOHN

Ludwick

WESTON

1872-1950

Pioneer Aviator and Overland

Traveller

POSTSCRIPT:

MONEY AND

ESPIONAGE

The press often called John Weston a “man of mystery” [1] and there was (and is!) no shortage of reasons for this claim. Chronologically, they start with Maximilian John Ludwick Weston’s identity.

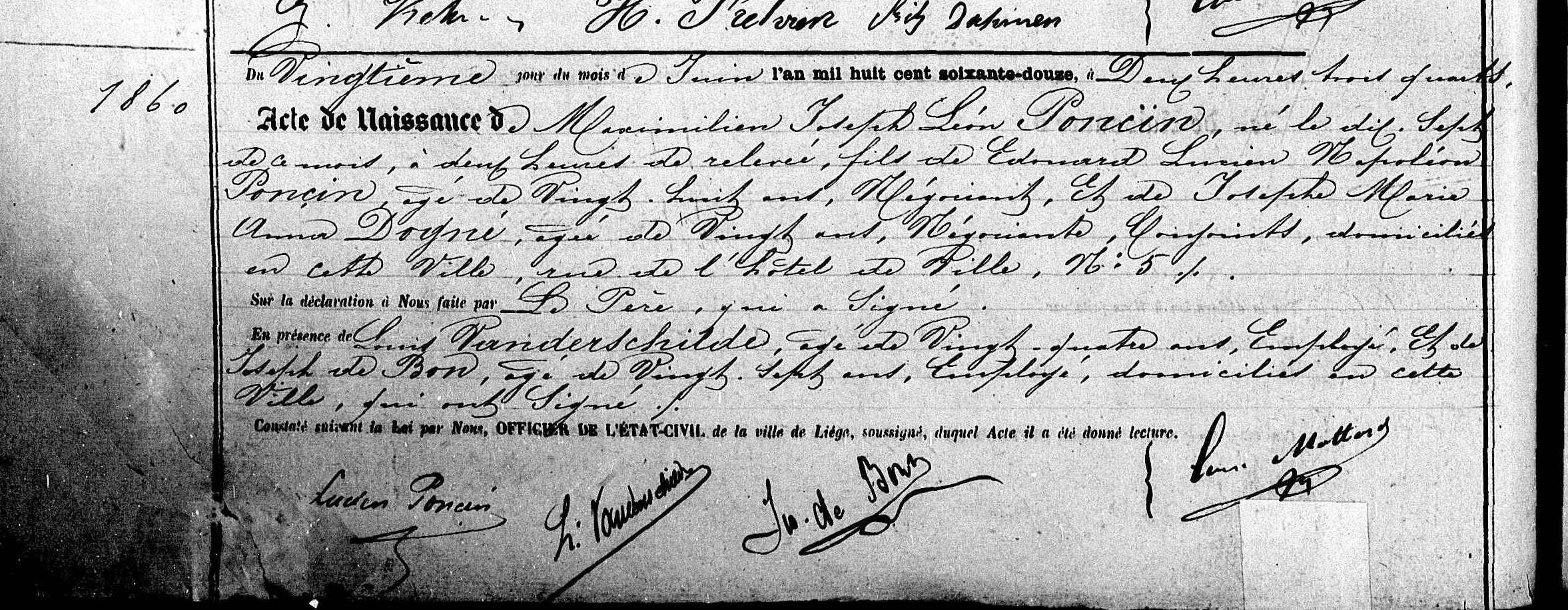

On 20 June 1872, in Liège, Belgium, a first child was born to Josephe Marie Anna Dogné and her husband Edouard Lucien Napoléon Poncin. From 1895 to 1902, Poncin would be one of Weston’s bosses at De Puydt and Poncin, a company which employed Weston as a “Partner and Technical advisor”. Lucien and Anna’s firstborn was named Maximilien Joseph Léon Poncin as the birth certificate shows [2] :

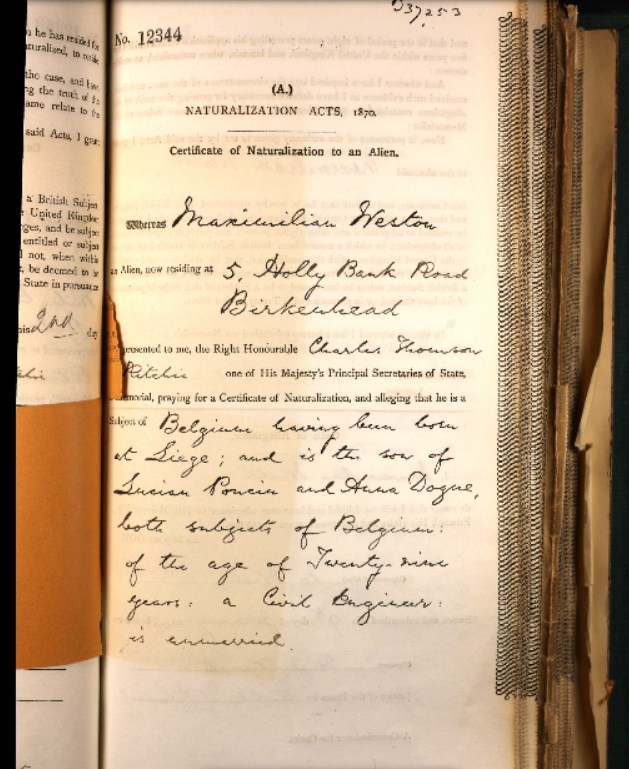

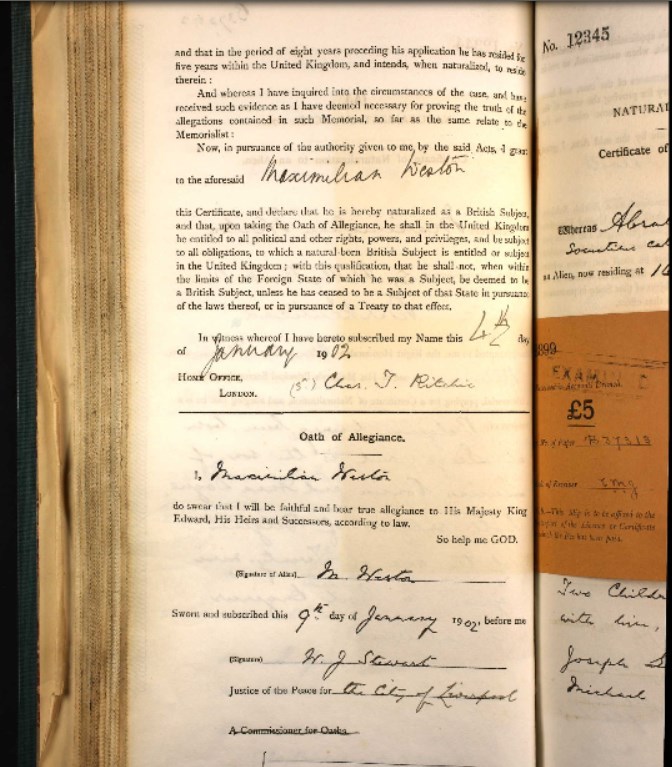

On 4 January 1902, “Maximilian Weston” of 5 Holly Bank Road Birkenhead signed the certificate which would give him British citizenship. He declared that he was a citizen of Belgium “having been born at Liège; and is the son of Lucian [sic] Poncin and Anna Dogne [sic]” [3]. The address identifies Maximilian Weston as the man we know as John Weston or Maximilian John Ludwick Weston.

Oberholzer says that Weston’s first name “was given after that of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, a good friend of his father’s [sic]” [4]. However there is no evidence for any part of this claim. Nor do we have any written corroboration of John Weston’s name during his first 28 or so years. There is no birth certificate and the earliest official record of either a forename or a surname is in this naturalization document.

Given that Weston claimed Poncin and Anna Dogné were his parents, it appears more likely that the name Maximilian derived from that of their son, not from the Emperor of Mexico. And if that is the case, it seems that John Weston added this forename to his original name which was probably either John Weston or John Ludwick Weston.

But is it possible that Poncin and Dogné really were his parents and that Weston was born in Liege? It seems highly unlikely. Weston was almost certainly born in 1872, 3 days before Maximilien Poncin. Even if Weston’s birth year was 1873 or 1874, the idea that Dogné was his mother does not make sense. In 1873, she already had an infant son and was preparing for the birth of her second son, Fernand Auguste Camille Poncin. He came into the world on 13 April 1874 [5A]. There are no Belgian records for a third Poncin child around this time: indeed, it appears from the excellent Liège records that Lucien and Anna had only 2 children [5B].

Why might Weston want to claim Belgian parentage and nationality and not even mention the forename John which he would use extensively in later life? Could it have something to do with the fact that, only months before, he had been fighting with the Boers against the British, probably under the name ‘John Weston’ ?

…………………………………

Weston’s income and wealth were and are a further mystery. They have even prompted the dramatic question – Was he a spy? In his lifetime it was commonly believed he was, in part because of his “retiring manner and apparent financial independence” [6].

At the time of his death, Weston’s estate was valued at £73,785 [7]. Measuring relative value over several decades is hardly an exact science, but today that might equate to £2,000,000… and it could be as much as £8,500,000 [8]! Yet it was not always the case that Weston was wealthy. In 1902 Weston appeared to be penniless [9]. By ~1907-1908, his financial situation seemed to have improved little. He was menially self-employed as “an itinerant thresher of mealies” [10]. Despite this, he was able to find sufficient capital to build an aircraft. Even more remarkably, in 1910-11 he took over 4 months away from paid employment to sail to Europe, to learn to fly, to study aeronautical engineering, and to buy engines and related kit which he then shipped back to South Africa. This at the same time as he had a young family.

After his return from France in 1911 and up to his 1914 enlistment in the forces, he was able to spend much of his time preparing for, and giving, flying demonstrations. He purchased several aircraft and related kit which he estimated cost £8,000 [11], at least £700,000 at today’s prices. It is clear that the demonstrations were not a financial success because they were all but abandoned by 1912 and a newspaper observed that flying displays are “not always remunerative… as can be testified by Mr. John Weston” [12].

At more or less the same time, Weston’s workshop suffered a major fire. In the aftermath Weston wrote “that the disaster is crippling me” [13]. Yet only a few weeks later he reported that “a consignment of work which I had ordered 9 months ago [has] arrived, so that, in addition to the machine [presumably an aircraft] I have now in hand, I shall be in a position of having 4 more [flying] school machines within six to eight weeks” [14].

The fire losses may well have been covered by insurance [15] but that does not answer the question of how Weston’s finances allowed him to assemble a fleet of planes in the first place, and to have purchased the components for four more. Nor how, by 1913-1914, he was able to visit Britain for a period. True, he was undertaking paid work at Willows in Cardiff but only for “a few hours daily”. “At the same time, I am conducting my experiments”, he wrote, without spelling out what they were. We know that he must have been flying too as he gained two pilot’s certificates in February 1914 [16]. This is not the life of a man with financial worries, at that family juncture when most people feel the pinch.

As we have seen, in the next phase of his life from 1914 to 1923, Weston was in the British armed forces. His income would not have been great but he appears to have been able to support a wife and three small children in Britain and to have sufficient disposable income to purchase a motor vehicle in the USA, ship it across the Atlantic, convert it into a motorcaravan, use it to make lengthy family journeys, and finally ship it back to South Africa together with Lily and himself.

On his return to South Africa he benefited from a British forces pension but it would have been modest. A family man would surely need to earn additional income. Yet there is no evidence of that in the 10 years before he paid out the enormous sum of £5,500 – at today’s prices something between £300,000 and £2,000,000 – to secure what became Admiralty Estates.

There could of course have been other sources of income in this period. We know that on 26 April 1928, Weston’s property at Brandfort was sold by public auction and acquired by Mrs Melanie Hofmann for the sum of £775 [17]. No doubt some or all of this was banked. It is also likely that his father was already dead and that John might therefore have had an inheritance from his mother who died in China that same year. We are told by Oberholzer and others that Weston had business interests but, though often mentioned, details of these are in short supply. Even though Weston had a reputation among his friends as “a hard businessman” [18] and “in business matters he gave no quarter and showed no sentiment” [19], we have no proof that any business interests actually existed let alone that they were significant and profitable.

Moreover, if they did exist and were generating a goodly income it would be surprising. Weston would have been one of very few businessmen and investors whose income held up during the greatest financial depression of the twentieth century.

And in the period 1928-1933 we know for certain that

-

Weston was not in paid work for almost 2 years. Firstly he went to and from China to wind up his mother and sister Lucy’s affairs. They had died from cholera whilst undertaking relief work [20]. Soon after that, he took a further ~18 months out for a family road trip across Africa and Europe;

-

he arranged for his three children to live in Britain and to study in British schools or colleges which must have been costly; and

-

following trans-Africa, he funded two passenger berths home, plus his vehicle’s cargo costs.

Yet in 1933, still in recessionary times, he was able to invest the equivalent of 7 Brandfort houses in Admiralty Estates – and then to purchase 36 miles of fencing, 500 head of cattle and goodness knows what else [21]. Where was this money coming from?

…………………………………

Had it been delivered to him in brown paper packets hidden under park benches?

During the Admiralty Estates years, the story went about that he ‘worked for Russia’ and had high seniority in the Soviet army. His frequent trips abroad greatly added to this belief [22], and so did Weston’s own actions. He appears to have contributed generously to the image of someone with an intriguing double life. For example, Mr Flanter – an old acquaintance from the Cape Town area – reported that

“During the First World War he was one of the three most famous master spies, the other ones being Trebitsch-Lincoln and Wickham Steed. For his services along these lines in the Aegean war theatre, the Greek Government of the day made him an honours admiral, as a result of which he would be piped aboard any warship, the Royal Navy included. He was a personal friend of Stalin, Chiang Kai Shek, F. D. Roosevelt, Churchill and many others. During the last war [1939-45] he was still engaged on some strange errands…

The next time he came to see me was about 1941. He looked very old and drawn and told me a rambling story of having been involved in a bombing raid and being wounded…

The next time must have been around 1942/43. He arrived hale and hearty and in very good shape… By now I had told my wife quite a lot about him… I took him up to the house and, naturally, the talk turned to the War. Stalin’s name came up and he said: ‘A very, very wily man. I should know. I have met him often enough’… He opened the little suitcase and after some rummaging produced a faded photograph of Stalin, some more Russians, and the Admiral [Weston himself], quite unmistakenly [sic].

A little while later the talk turned to Churchill. ‘Now there is a great man, and his wife the most charming of women,’ said the admiral… and up came a picture of him and the Churchills having tea. The next one was him with Mr and Mrs Chiang Kai Shek in a boat on the Yangtse river, then Mr and Mrs Roosevelt. By that time we were very shaken… He then told us how he was spying during the First World War for the British and that he had an appointment to meet Trebitsch-Lincoln and Wickham Steed at some forlorn railway station in Siberia. Only the three were so well disguised that they did not recognise each other…” [23].

Another of Weston’s acquaintances, a Mr Baer of Eastern Cape Province, knew Weston from the days of the aviator’s flying displays. Sometime during 1932, whilst travelling in their motorcaravan, John and his wife visited Baer. A few days were spent with him during which time (according to the host) they had “very intimate talks” and he was told (presumably by Weston) that the latter was in the employ of the British secret service and that he was on a mission to China [24].

Oberholzer’s enquiries of various British government departments failed to reveal any evidence that Weston may have been a spy [25] and in the absence of such evidence – and indeed anything even moderately supportive of the proposition – it seems reasonable to assume that Weston’s financial independence did not arise from espionage.

…………………………………

‘Weston as spy’ may be just one chapter of the dubious autobiography that Weston himself authored but never published. It is a tale that owed much to Weston’s apparent talent for inflating his status and gilding an already colourful biography. The adoption of an extravagant name may well be the first chapter. But there is more.

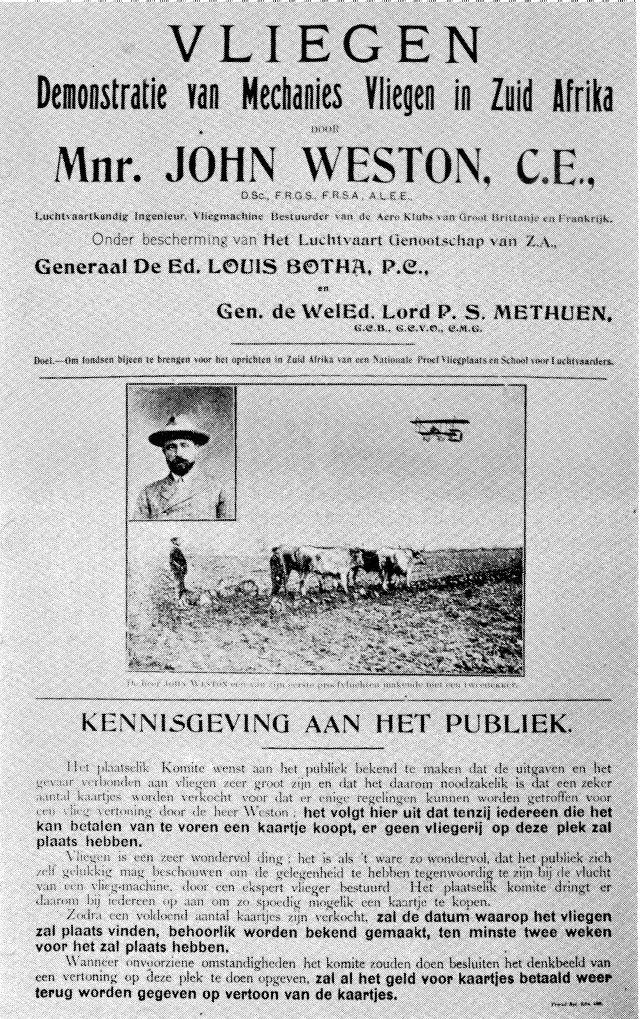

There is evidence of status inflation as early as 1911-1912. Weston was advertising his flying displays throughout southern Africa and a poster in Afrikaans headed “VLIEGEN” states these will be given by “John Weston, C.E., D.Sc., F.R.G.S., F.R.S.A., A.I.E.E.” [26].

Today, and in this context, the letters CE would signify Chartered Engineer – but not in the early 1900s: “there was no title such as a ‘Chartered Engineer’ prior to WW1 and when the terms did come about in the 1920s they were more specific i.e. Chartered Civil Engineer [or] Chartered Electrical Engineer” [27]. An expert from the relevant professional body writes that perhaps “The letters CE simply stand for Civil Engineer and do not denote membership of any professional body… [However] I cannot see him listed as an ICE [Institution of Civil Engineers] member which [is] not surprising as he would have used the appropriate letters after his name on the poster. Therefore John Weston could have been referring to himself as a Civil Engineer on this poster… However, as he was a member of the IEE I wonder why he would use CE after his name?” [28].

Weston was certainly an Associate of the Institution of Electrical Engineers (AIEE) and a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society (FRGS) but there is no evidence that he was FRSA, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, though he was certainly a member [29].

Moreover it is impossible to believe he was a D Sc (Doctor of Science), despite Oberholzer and several others referring to him as ‘Dr’. Though Oberholzer says “there seems to be no doubt that Weston did in fact obtain a D.Sc. degree”, there is considerable doubt.

Where was this degree obtained? Oberholzer acknowledged he did not know. However he did know that, when Weston applied for associate membership of The Institution of Electrical Engineers in 1902, his only claim was that he had “pursued his technical studies during the period 1888-1894” [30]. Weston made no claim either to have received a vocational or a professional qualification or a degree, let alone a postgraduate qualification. And how could he have gained the latter? Weston completed his studies in 1894 when he was only 22 [31] and there is no evidence that he went back to them later.

‘Dr Weston’ appears to be a myth to sit alongside another that appeared 10 to 20 years later: ‘Admiral Weston’.

Countless texts contain countless references to Admiral or Rear Admiral Weston when, as we have seen, he was awarded the entirely honorary rank of Vice Admiral – and that in the Royal Hellenic Navy, a fact rarely mentioned whenever the title is used.

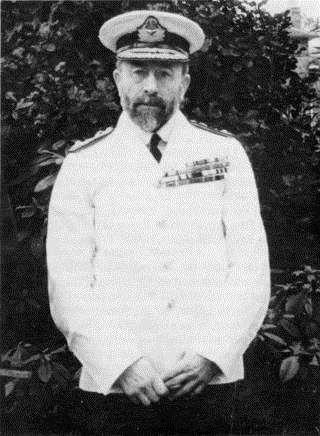

However, it is little wonder that people thought he held the rank of admiral – and in the British navy. Weston himself came up with the name Admiralty Estates and inscribed “Rear Admiral John Weston” on its headed notepaper [32]. He was also wont to wear a rather impressive but ‘unofficial’ admiral’s uniform, as this photograph reveals [33]. The peaked cap bears the emblem reproduced with greater clarity at the head of this page. It is not Greek: it is that worn by an officer of the (British) Royal Naval Air Service [34].

…………………………………

How was it possible for Weston to become, in the eyes of so many people, a doctor, an admiral, and a spy?

Perhaps because Weston’s lengthy, successful and even admirable war service would deflect forensic interrogation of his military rank. In addition, his education and his military service were undertaken a world away from the country in which the myth of his elevated rank became current.

We should also acknowledge that Weston’s aeronautical achievements in the early years of the century had amply demonstrated he was a bold and fearless pioneer and an inventive and more than competent engineer. Perhaps that meant he was unlikely to be challenged on whether he had the right pieces of paper. He really did have qualities, skills, experience and knowledge which might have encouraged people not to question his qualifications, then his titles and his tales of espionage, and later even his claimed personal intimacy with world leaders. One example: Weston could speak Russian, so the proposition that he knew Stalin might have rung true. This example is noteworthy for another reason: Weston’s claims often related to contexts and parts of the world with which he really was familiar whilst others were not.

Unfortunately, whilst this explanation of how Weston successfully elevated his status may be plausible, it does nothing at all to help us understand his apparent financial independence and his actual wealth.

The espionage explanation may not be tenable, but is there a better one?

[1] Oberholzer op cit

[2] “Belgique, Liège, registres d’état civil, 1621-1914”, database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:27NL-MT9 : accessed 13 October 2015), Maximilien Joseph Léon Poncin, 1872.[3] Ancestry.com. UK, Naturalisation Certificates and Declarations, 1870-1912 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

[4] Oberholzer op cit

[5A] “Belgique, Liège, registres d’état civil, 1621-1914”, database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QK9G-GRR3 : accessed 13 October 2015), Fernand Auguste Camille Poncin, 1874.

[5B] Only 3 years after his last-known contact with Liège (and with the Poncins?), Weston would name his firstborn ‘Anna’.

[6] Oberholzer op cit

[7] Ibid

[8] Figures here and later were calculated using http://www.measuringworth.com. For purposes of calculation, “today” was 2012.

[9] On this page of the website, footnotes are not provided where reference is being made to information cited on previous pages.

[10] Oberholzer op cit. ‘Mealies’ is a coarse flour made from maize/corn.

[11] Ibid

[12] The newspaper The Friend (23 April 1912) quoted by Oberholzer op cit

[13] Oberholzer op cit

[14] to [17] Ibid

[18] Jackson C. 8 May 1951. Affidavit, Estate of M J L Weston, papers in the State Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

[19] Rencken Trau. 4 May 1951, Affidavit, Estate of M J L Weston, papers in the State Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

[20] Oberholzer op cit. It seems likely that Weston sailed to China in late 1928. There is a record of him taking a ship from South Africa to San Pedro (Los Angeles) on a Japanese ship. This was a very unusual journey for Weston: he is invariably is to be found sailing the Atlantic. This may have been the first leg of his journey to China. Ancestry.com. California, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1882-1959 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2008.

[21] M J L Weston, undated but circa 1938, Preliminary Information regarding a business undertaking

[22] Oberholzer op cit

[23] to [26] Ibid

[27] Institution of Electrical Engineers, 2 April 2014. Personal communication with the author

[28] Ibid, quoting the views of the archivist at the Institution of Civil Engineers

[29] Personal communication to the author from the RSA

[30] Oberholzer op cit

[31] Ibid

[32] M J L Weston, undated, Notepaper for Admiralty Estates, Estate of M J L Weston, papers in the State Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

[33] Oberholzer op cit

[34] Ibid, but also identified as such in Tidy, Major D P, 1982, They Mounted up as Eagles (A brief tribute to the South African Air Force), The South African Military History Society, Military History Journal Vol 5 No 6