Maximilian

JOHN

Ludwick

WESTON

1872-1950

Pioneer Aviator and Overland

Traveller

WORLD WAR 1

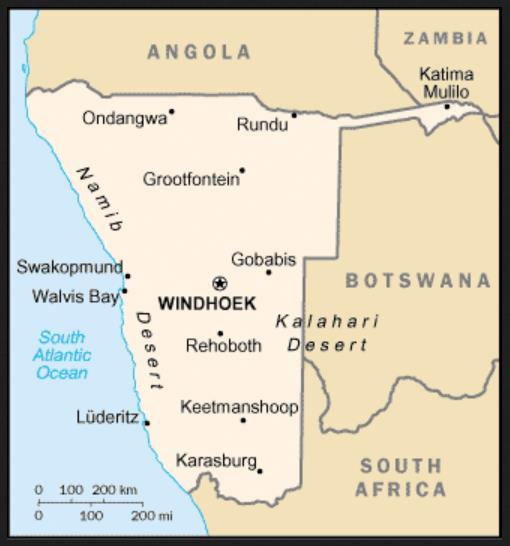

Around August 1914 Weston joined the South African forces fighting the Germans in the South West Africa (SWA) campaign [1]. “The responsibility for providing and maintaining airstrips and hangars was given to the man who may have been the pioneer of aviation in South Africa: John Weston” [2].

His military status at this time is unclear. Oberholzer quotes JGW Gordon as having met Weston “somewhere in the middle of South West Africa during the campaign [against German forces]” [3]. Gordon said Weston was “in the uniform of a lieutenant of the Royal Naval Air Services” [sic], but Oberholzer corrects this: Weston “was in fact in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve” (RNVR). Yet neither of these observations is totally convincing. The Royal Naval Air Service was not represented in the SWA campaign, other than by its Armoured Car Division from April to June 1915 [4]. Neither was Weston in the (British) RNVR at this time [5]. Was he in the South African RNVR?

Whatever, we can be certain that, on 6 February 1915 towards the end of the short SWA campaign, Weston joined the South African Air Corps (SAAC) as a lieutenant [6]. This was the day after the corps was founded [7] and Weston’s SAAC record contains two additional snippets of information: firstly the dates “6-2-15 – 31-7-15”, and secondly, “Embarked per S.S. “Erna Woermann” for Northern Force 21 3 15”.

In early 1915 SA forces held coastal positions which allowed troops such as Weston to take ship to link up with the army led by General Louis Botha in the north of SW Africa [8]. A fellow soldier Eric Moore Ritchie kept a diary and in it describes a similar journey. It seems likely that Weston followed much the same path:

“We reached Cape Town on the 15th [January 1915]… Up till that time South Africa itself had never put an expeditionary army, to be shipped by sea, on a war footing, and at Cape Town the work of equipping the South-West African Expeditionary Force was carried on and finished during the four weeks we were there…

On Friday, the 5th of February, we struck camp at sunrise. All our horses had been shipped the day before; we proceeded to the Docks by train and on foot… we were three hours on the heavily laden transport wagons before we got to the transport Galway Castle… And then eighteen hundred more warriors filed down the quays and, like Mr. Jim Hawkins, came aboard, sir…

At 8 a.m. on the 9th we arrived at Walvis Bay [SW Africa]. General Botha, who, with his Chief of Staff, A.D.C.’s, etc., had embarked at the Cape on the auxiliary cruiser Armadale Castle, arrived at Walvis later in the morning…

We left the Galway Castle on the 11th, disembarking into lighters, to be towed up the coast to the occupied German port of Swakopmund… the first Headquarters of the Northern Force, Union Expeditionary Army” [9].

Weston arrived later, as the tide was beginning to turn in favour of the South Africans [10]. Whilst little is recorded of Weston’s role at this time, it might reasonably be assumed that his earlier SWA experience in providing and maintaining airstrips and hangars [11] would be useful. The Corps was obliged to put in place basic infrastructure before flying could be contemplated and actually it was not until 1 May that the first aircraft actually arrived, over a month after Weston. Two Farman biplanes came, and even then they could not be used because they were found to be damaged [12]. Perhaps Weston’s aircraft engineering expertise also came into play at this point.

Notwithstanding the difficulty of pinning down Weston’s role, that of the SAAC is clear:

“… on 6 May 1915 the Corps commenced operations, mainly reconnaissance…. General Botha, who had previously depended on mounted men for reconnaissance, declared ‘Now I can see for hundreds of miles’. The aircraft were also used on bombing raids and the South Africans were able to out manoeuver [sic] the Germans, leading to their surrender three months later after [sic] the South African Aviation Corps entered the campaign” [13].

The bombing raids are not mentioned by our troop diarist Ritchie. The importance of reconnaissance is:

“[By mid-June 1915, Botha had] the Aviation Corps in full working order – had aerial eyes wherewith to be guided through a subtropical bush country very full of possible dangers…

On June 24 … [the] enemy had retreated. It had been predicted with the utmost confidence that the Germans would here put up a fight. So confidently was this expected that the Commander-in-Chief would hardly believe it when the aeroplanes returned and reported that there were about half a dozen Germans left in the place. Yet that proved to be exactly the fact, and so greatly impressed was General Botha with the accuracy of the observations on this occasion that he emphasised that the skymen were to receive every possible assistance for the future” [14].

In another account, we have the only specific reference to what Weston was doing. He was not flying: he was supporting aerial reconnaissance:

“The first real flight [by the SAAC]…took place on Thursday, May 6th, when Lieut. Carey-Thomas, accompanied by Lieut. Clisdal, left Walfish [Walvis], for Garub, via Swakopmund. The erection of beacons as far as the latter place was in charge of Lieut. Weston and Sergeant Williams” [15].

The Germans capitulated on 9 July 1915 [16] and it therefore seems likely that the date “31-7-15” in Weston’s SAAC service record refers to the end of his active service with the Corps. However, in mid-September a photo shows him at Hendon, London, England, then a very important aerodrome and air training location – and he is wearing the uniform of the South African Aviation Corps [17].

In mid to late 1915 the Corps itself underwent a major change and its personnel shifted location dramatically. It “ceased to function as a separate unit from the end of the South West African campaign in October 1915 [though it was not officially disbanded]… Members of the Corps were incorporated into 26 Squadron of the [British] Royal Flying Corps. The Squadron saw service in East Africa in support of South African forces under General Jan Smuts” [18].

However, when the former SAAC personnel left for East Africa in December [19] there is no evidence that Weston was with them. Given his proud pose in the Corps’ uniform, it seems likely he had a commitment to that regiment and it is possible that he was given the option of serving under Smuts. So why might he take a different route? And why was it, with the war raging, that he did not join another fighting group until the middle of the following year, 1916?

The reason may have been personal. Soon after the end of his active SWA service on 31 July 1915, Weston lost no time in heading for Britain. However, he was not alone. The Saxon docked at Tilbury on 9 September 1915 and on board was the entire Weston family, including 3 month old Max [20]. Weston was 43, a man of mature years with family responsibilities unlike so many of his SAAC comrades: one of the most famous SAAC pilots of this period, Kenneth Van Der Spuy, was only 23 [21]. As the next few years showed, Weston was keen to fight, but perhaps not in East Africa when his wife, two school age girls and a tiny infant son were in Britain.

His Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) record of service shows that, on 1 July 1916, he was commissioned as a Temporary Sub Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. His duties with the RNAS together with seniority in that rank commenced on the same date. His first appointment was to “No.3 Aeroplane Wing, Manstone [sic]” [22]. On 28 September he was re-appointed, but this time as Temporary Acting Lieutenant [23].

Manston in Kent was home to No.3 Wing at the time of Weston’s original commission and in July 1916 the Air Ministry wrote to “Commanding Officer No 3 Wing RNAS Manston”:

“The following procedure is to be carried out with regard to the formation of the remainder of 3 Wing for service in France. The training of the various squadrons will continue during the summer months. [sic] i.e. up to the 1st October, by which date all officers and men will proceed to No 3 Wing base in France” [24].

This memorandum goes on to say that the troops would be heading for Vesoul. This town is only 34kms from Luxeuil-les-Bains which was “No 3 Wing base in France” and thus the troops’ final destination:

“The wing [No. 3 (Naval) Wing] was assembled… during the spring of 1916 and arrangements were made with the French for it to operate from a field at Luxeuil-les-Bains, in the Vosges region northwest of Belfort, within easy flying range of the heavily-industrialized Saar area and northern Lorraine, where much of the German iron and steel production was concentrated” [25].

It has been claimed that whilst in France he was present at the battle of Verdun, that he served as a balloonist and aeroplane pilot, and that he undertook aerial mapping [26]. However these find no foundation in his war record which, as we shall see, is very detailed. The RNAS does not even appear to have been involved at Verdun [27] and Weston’s Luxeuil base is some distance to the south.

His duties there are clear. From 28 July 1916, Weston qualified for an allowance of one shilling per day for French/English interpreting duties [28]. His linguistic skills gained over more than a decade in Belgium would be of value in easing the establishment of a new base on friendly but nonetheless foreign soil. And it seems likely that Weston brought even more to the table. His many years of living within 50kms of the German border meant he had a far better grasp of the geography of the target area than his comrades or commanders.

Luxeuil’s purpose was the aerial bombing of western Germany. “It was initially proposed that the wing would consist of 60 aircraft, later to be expanded to 100 machines” [28B] and Weston was to become focussed on bombing during the later part of his Luxeuil service. In a memo to No 3 Wing Commanding Officer Elder dated 9 January 1917, Weston briefs the CO on “the efficiency of our… squadrons” and makes reference to many bombing raids on industrial and other strategic targets in Germany – in the Saar and Moselle valleys, on Mülheim, Oberndorf and Dillingen [29].

This briefing must have been one of Weston’s first acts following his appointment, on 5 January 1917, for compass and intelligence duties [30]. A couple of months earlier some of the RNAS aircraft staff had moved to Ochey, south-west of Nancy [31] but two RNAS memoranda dated 25 February indicate Weston remained at Luxeuil [32].

Weston’s core duties as compass and intelligence officer were of some consequence. The Fleet Air Arm Museum says that

“Within the numerous tasks which had to be shared out amongst squadron officers, the calibration (and, therefore, accuracy) of aircraft compasses was an important one. It was closely linked to the provision and up-dating of maps of the area of operations. The intelligence task within a squadron was closely related to both the conduct of flying operations and, based on reports by pilots and observers, to the marking of maps with new intelligence (of both the enemy and the geography of the area of operations). So it would not be unusual for a suitably qualified officer to be given some or all of the ‘compasses, mapping and intelligence’ tasks in a squadron. Weston, with his flying and technical background would appear to have been admirably qualified and suitably employed in the role. He may well have flown as an observer but [the Fleet Air Arm Museum has] not found any evidence of this. He would certainly have been required to brief observers on what he expected them to achieve on a flight” [34].

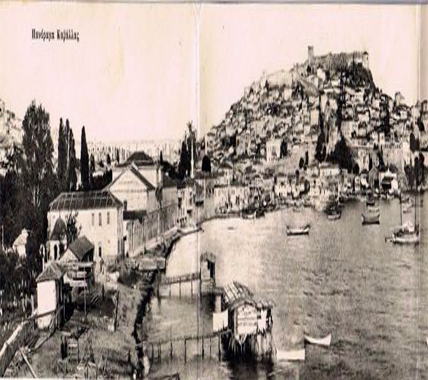

On 2 April 1917 Weston was appointed to No. 2 Wing for compass duties at East Mudros on the island of Lemnos in Greece [35]. Mudros was to be Weston’s principal war posting .

A Greek island in the eastern Mediterranean, Lemnos is close to the western end of the Dardanelles (in modern Turkey) and within easy reach of eastern Macedonia (in modern Greece). Mudros (or Moudros) was an important military base during the Gallipoli campaign which pre-dated Weston’s European service. It went on to support later fronts against the Ottoman Empire, including that in Macedonia. From Mudros passenger and goods traffic was regulated in the eastern Mediterranean. It housed garrisons and hospitals and was a base for aircraft as well as ships making use of the good harbour. Henri Farman planes were serviced there [36] which must have given pleasure to Farman’s former pupil and collaborator.

During 1917 Weston was also in Egypt for a short period. On 8 June he was transferred to “intelligence duties” at the Seaplane Depot, Port Said, but then switched back to Mudros and to compass duties on 3 September [37]. The confidential report on his service in early 1917 states that he was “A thorough and efficient mapping officer very energetic and hardworking”. For the later part of the year, the report says that he was in charge of all “aerodrome constructional and draining work, roadmaking… A very capable “E” officer” [38].

Sometime in the later part of 1917, probably 11 August but the handwritten record is unclear, he was recommended to be appointed as Technical Officer to the Paris Air Station for which he “Has all the necessary qualifications” [39]. We know this came to nothing because in early 1918 the Admiralty recorded him still at Mudros. Weston was at the “Repairs Base” [40] but no evidence has been found to indicate that he was fulfilling an engineering role, despite the fact that before the war his attachment to flight was firmly technical: “Yes, I have made hundreds of flights over country [sic], and have been, say, for eighty minutes in the air. But, of course, I have looked on flying from [a] technical, not from an aerobatic point of view” [41].

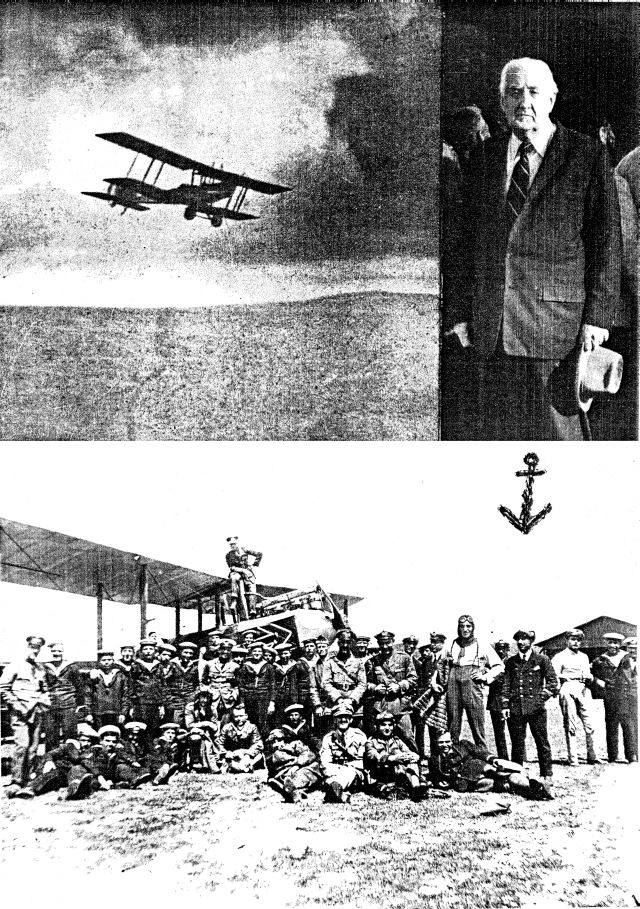

However, handwritten notes on the back of photos deposited at the South African National War Museum and dated 1969 [42] give further details of what Weston’s duties were – and describe a remarkably different role than that suggested by “compass duties”. The author of the notes was Thanos Murray-Veloudios (pictured as an older man, below, standing) , a pilot and officer in the Royal Hellenic Naval Air Service (RHNAS). Today he is acknowledged as one of six “Notable personnel” of that Service [43].

Some background at this point. The creation of the RHNAS began no earlier than 1916:

“Political struggles within Greece hindered the development of air arms in their services, until 1916 when a provisional revolutionary government… welcomed Allied participation in Macedonia against the Bulgars and their Turkish allies. A new air arm for the Royal Hellenic Navy was planned with naval personnel being sent to the Royal Naval Air Service at Mudros for training… Greek officers first became operational with “A” Squadron, R.N.A.S., operating from the island of Thasos… During March [1917] further Greek officers and some N.C.O.s reached “A” Squadron and participated in operations. Three months later, with further reinforcement, the Greeks formed a squadron of their own, initially known as “The Greek Squadron” and then designated “Z” Squadron, with the intention of naming any further Greek squadrons alphabetically in reverse order…. For the first week of July the majority of the personnel of “Z” Squadron was transferred to Mudros” [44].

These airmen – seen above in 1917 at Mudros – were under direct (British) RNAS command:

“”Z” Squadron (Greek: Ζήτα Σμήνος)… was created by Greek personnel under direct Royal Naval Air Service command and carried out operations in the northern Aegean, based at Moudros (Lemnos) and Thasos. Moreover, a joint Army-Navy flight school was established at Moudros” [45].

“When Greece joined the Triple Entente in World War 1… Moraitinis [the most famous of the Greek pilots] was transferred to the northern Aegean, where he served under the command of the British Royal Naval Air Service” [46].

With reference to the group photograph (left) also lodged at the War Museum, Murray-Veloudios gives Weston a key role in the RHNAS and Z Squadron. He wrote that

“This [group of airmen in the photo] is one of the flying units of the Royal Hellenic Naval Air Service, which was originally organised in 1917 by Captain John Weston of the British RNAS, from South Africa, jointly with Lieutenant Commander A. Moraitinis RHN, in Mudros on the Island of Lemnos in north eastern Greece… Right in the middle of this photo in the front row… is the C.O. of this unit, Lieutenant Pilot Thanos Murray-Veloudios RHNAS then 22 years old, who had his training by Captain John Weston, like most of these pilots flying officers [sic] and engineers of the Greek Navy as depicted here” [47].

So according to Murray-Veloudios, Weston was not only a major player in the establishment of the RHNAS, he was a principal trainer of pilots, crew and engineers. However he also proposes that Weston was active as a bomber pilot. Referring to another photograph (above, top left), he writes:

“This is an early type of an english aeroplane, Bleriot Experimental B.E.2E with which Captain John Weston RNAS from South Africa bombed repeatedly in 1917 the Dreadnoughts [sic] Breslau and Goeben, originally German, turned over to Turkey [and then re-named Midilli and Yavuz Sultan Selim respectively – though still manned by Germans [48]], when attacking the turkish arsenal Nagara in the Dardanelles Straits north west of the Aegean Sea” [49].

The Breslau and Goeben (left) were ships of some consequence: “Few ships have influenced history more than the Goeben and her companion, the light cruiser Breslau” writes one commentator [49B].

Although Murray-Veloudios cites the wrong year for the action, the historical record confirms the use of air power in this incident:

“[The] Goeben [was] damaged 20th January 1918, Aegean Sea, off and within the Dardanelles, Turkey – by 3 British-laid mines, followed by aerial bombs. [Not long after] ‘Breslau’ hit a mine. ‘Goeben’ was taking her in tow when mined again, and then the cruiser detonated four more mines in quick succession, settling fast at 0900 with most of her crew. ‘Goeben’ headed back for the Dardanelles, hitting a third mine, and then half way in and listing, ran hard aground at Nagara Point just before midday, still on the 20th” [50].

Notwithstanding the testimony of Murray-Veloudios, one group of experts is not convinced of the veracity of his account of Weston’s roles:

“In the April 1918 AFL [Air Force list]… John Weston is shown as a Lieutenant RAF in the Administrative Branch with seniority 1 Apr 1918. In the March and April 1919 AFLs he is shown as a Major RAF in the Administrative Branch (Ad) with seniority 1 Jan 1919. In the October and November 1919 AFLs he is shown as a Squadron Leader in the Technical Branch (T) with seniority 1 Jan 1919. This confirms my contention that he never flew as an RAF pilot while serving in the RAF – to do this he would have had to be in the Aeroplane (A) or Aeroplane and Seaplane (A&S) Branches of the service. This reinforces my view that he was a Technical Instructor to the Greeks (albeit with useful piloting knowledge) [rather than their flying instructor]” [51].

But in the fog of war, on a small island in the eastern Mediterranean…? And is it likely that Murray-Veloudios would get such important, personal information wrong?

On 1 April 1918 the Royal Air Force was created by the merger of the Royal Naval Air Service and the Royal Flying Corps. Accordingly Weston was transferred to it with the rank of lieutenant. In August he was elevated to the temporary rank of major “whilst specially employed” [52]. This special employment was most probably his posting to the British Naval Mission to Greece as Head of the Technical Section [53]. According to one source, this appointment commenced “when the Armistice came” (ie 11 November 1918), and “S/Cdr. John Weston” replaced Flight-Commander F W Gamwell at the Mission with a remit for “air matters” [54]:

“By then [November 1918] a large number of aircraft were controlled by the Mudros base. As there was a surplus of aircraft in Britain only a few were shipped home. By arrangement with the Greeks, all aircraft used for their training and provided for operations were made over to them as a free gift and other aircraft collected at Mudros from the various Aegean bases were offered at a nominal sum. On the advice of the British Mission a few Avro 504Ks were shipped out for primary training. Altogether 118 aircraft were passed to the Greek Government” [55].

Being responsible for “air matters”, Weston must surely have been closely involved in the planning and delivery of this astonishing gift.

On 9 January 1919 it was announced that John Weston had been made a substantive major “in recognition of distinguished service” [56]. However he did not receive the Distinguished Service Order as suggested by one source [57] and retirement from military service would not be for another four years, all of which seem to have been spent with the Naval Mission [58].

In July 1919 Weston received the first of two honours from Greece when he was awarded the Cross of Officer of the Royal Hellenic Order of the Redeemer [59]. Four years later he was given the rank of Vice-Admiral in the Royal Hellenic Navy for services rendered to the (Greek) Ministry of Marine whilst serving as a member of the Mission. The letter confirming this honour “from Athens” (ie from the British Embassy) was dated 13 September 1923 [60]. It seems extraordinary that Weston should have been given this elevated title when others with greater seniority in the Mission had to make do with the Cross [62]. Perhaps the answer lies in the astonishing largesse over which Weston presided, but his significant contribution to the formation of the RHNAS and the training he gave to large numbers of Greek air force personnel may also have helped.

In addition, Murray-Veloudios gives an insight into Weston’s role at the Mission which would certainly have endeared him to the Greeks. The 1918 Armistice was not the end of war in the Aegean. From 1919–1922 Greece and Turkey waged a bloody conflict [63] during which Weston was allegedly no deskbound military attaché but an active participant supporting Greece. Referring to a photo of himself alongside an aircraft, the 75 year old Murray-Veloudios records:

“[This shows] Group Captain Thanos Murray-Veloudios of the Royal Greek Air Force now (1969) retired… who in the summer of 1920, with the aeroplane Bleriot Experimental B.E.2E, alloted [sic] by the South African Captain John Weston, conquered alone the city of Brussa [a mis-transcription of Bursa] at the foot of the Bithynian Mount Olympus in Asia Minor, by hoisting there himself, first, the Greek National Flag…” [64].

That the successful Greek campaign in the summer of 1920 included action around Bursa is confirmed by the historical record [65].

Major John Weston left the services on 22 November 1923. He had been awarded the honours already mentioned and two medals, the Victory and the British War Medal [66]. He was permitted to retain the rank of major [67] and his RAF record concludes with “Willing to serve anywhere in any capacity” [68].

[1] Oberholzer op cit. SWA is now Namibia.

[2] L’Ange, Gerald. Urgent Imperial Service: South African Forces in German South West Africa 1914-1915. Ashanti. Rivonia, South Africa. 1991

[3] Oberholzer op cit. Gordon JGW. The Men who Blazed the Trail. The Star. Johannesburg. 26 March 1935

[4] Information supplied by Fleet Air Arm Museum Archive Department and Research Centre

[5] Ibid

[6] John Weston SAAC service record. (South African) Department of Defence Documentation Centre (Archives)

[7] http://www.saairforce.co.za/the-airforce/history/saaf/south-africa-aviation-corps

[8] http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol132hp.html

[9] Ritchie, Eric Moore. With Botha In The Field. Longmans, Green and Co. London. 1915

[10] http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol132hp.html

[11] L’Ange op cit

[12] Hodgson Hartley, J. The S.A. Aviation Corps and their doings in S.W. Africa. Flight. 3 December 3 1915

[13] www.saairforce.co.za/the-airforce/history/saaf/south-africa-aviation-corps

[14] Ritchie op cit

[15] Hodgson op cit

[16] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_South-West_Africa#World_War_I

[17] Oberholzer op cit

[18] www.saairforce.co.za

[19] http://www.sapfa.org.za/history/history_2.php

[20] The National Archives. UK Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960. Accessible at www.ancestry.co.uk

[21] http://www.vanderspuy.co.za/indiI01153.html

[22] Public Record Office File Airl/2512. Disposition of Officers of the Royal Naval Air Service 11th September 1916, and The London Gazette. 4 July 1916

[23] Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) Pay and Appointing Ledger. Fleet Air Arm Museum Archive Department and Research Centre

[24] No 3 Wing R.N.A.S. 1916-1917 Britain’s First Strategic Bombers Appendix O Part 1. Fleet Air Arm Museum Archive Department and Research Centre

[25] Dodds RV. Britain’s First Strategic Bombing Force: No. 3 (Naval) Wing. The Roundel, July–August 1963, Vol. 15, No. 6.

[26] Klein op cit and Oberholzer op cit

[27] Information supplied by the Fleet Air Arm Museum Archive Department and Research Centre

[28] Ibid

[28B] Peason, Bob. More Than Would Be Reasonably Anticipated. http://www.overthefront.com/WWI-Aviation-No-3-Wing-Royal-Naval-Air-Service-p1.php

[29] No 3 Wing R.N.A.S op cit

[30] Fleet Air Arm Museum op cit

[31] Dodds op cit

[32] Fleet Air Arm Museum op cit

[34] Ibid

[35] Public Record Office File Airl/2512 op cit

[36] www.iwm.org.uk/collections/ and www.fhindexes.co.uk/cwlewin.pdf

[37] Fleet Air Arm Museum op cit

[38] Public Record Office File Airl/2512 op cit

[39] Ibid

[40] Oberholzer op cit

[41] To Storm the Skies. Mr John Weston, Air Pilot. First South African Aviator, Cape Argus, 7 March 1911

[42] Murray-Veloudios, Thanos. Weston J file, South African National War Museum

[43] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hellenic_Naval_Air_Service

[44] Robertson, Bruce. “Z” (Greek) Squadron R.N.A.S: Pioneer Greek naval aviators at war. Air Pictorial Feb 1988

[45] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hellenic_Naval_Air_Service

[46] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aristeidis_Moraitinis_%28aviator%29

[47] Murray-Veloudios op cit

[48] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SMS_Breslau

[49] Murray-Veloudios op cit

[49B] http://www.cityofart.net/bship/turc_yavuz.html

[50] http://www.naval-history.net/WW1NavyTurkish.htm

[51] Fleet Air Arm Museum op cit

[52] Oberholzer op cit and The London Gazette. 2 August 1918

[53] Oberholzer op cit

[54] Robertson op cit

[55] Ibid

[56] Oberholzer op cit and Supplement to The London Gazette. 1 January 1919

[57] Anon (but thought to be written by Kathleen and Karl Rein-Weston) op cit

[58] Oberholzer op cit

[59] Flight. 31 July 1919 and Supplement to The London Gazette. 15 July 1919

[60] Oberholzer op cit and RAF record of service for John Weston

[62] http://www.medals.org.uk/greece/greece001.htm

[63] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greco-Turkish_War_(1919-1922)

[64] Murray-Veloudios op cit

[65] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_the_Turkish_War_of_Independence

[66] Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Medal Rolls. The National Archives microfilm publication ADM 171, 202 rolls. The National Archives of the UK, Kew, Surrey, England/

[67] The London Gazette. 4 December 1923

[68] RAF record of service for John Weston